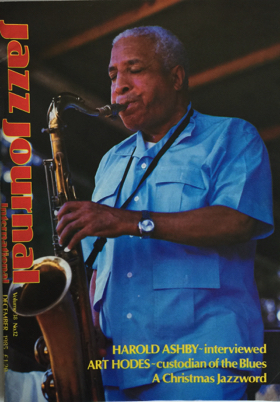

Harold Ashby Talks to Eddie Cook

Jazz Journal May 1985 Vol. 38 No. 12

Apart from recognising him as a former member of the Duke Ellington Orchestra and perhaps from knowledge of one comparatively recently released album under his own name, few people in UK are likely to be familiar with his work I told him, so how had his career begun?

“Well, I'll tell you the whole story, I was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on March 27 1925. I went to grade school and then began to play clarinet in the high school band you know - for an hour a day. Then I went to vocational school and played tenor saxophone. I used to babysit for my brothers - I had two brothers, Herbert and Alec, who were musicians. Herbert was an alto player and Alec played trumpet; I had two other brothers and one sister. They both played with Ben Webster and studied violin in high school. So from the high school I went to junior college for a couple of years before I went to vocational school and studied saxophone - three hours a day. When I got to 18 I went into the navy, I didn't play.”

Not in a service band? I queried. “Well no, I wasn't a professional musician then - I remember going to dances and things like that, that's where I heard Duke Ellington and bands like that - on a Sunday.”

In fact Ashby lost his mother when he was about seven or eight years old and his father who had worked through the depression as a janitor, died when he was 18. Harold's earnings from summer jobs in a grocery store were useful in a large growing - up family, and later he worked for his uncle before he was drafted. Kansas City was a wide-open place when he was a boy, and he heard the Basie band with Lester Young, Andy Kirk, Hot Lips Page, Joe Turner and many others, of whom by far the most influential was Ben Webster.

“When I went into the navy I was stationed in Chicago, and there was a place there where Ben Webster was playing, together with J. C. Higginbotham, Red Allen, Don Stovold and I used to go down and listen to them. (The Downbeat Club '44-'45) I was about 18 or 19 years old then. When I got out of the service I went back to Kansas City and I started playing then with Tommy Douglas, professionally.”

“Douglas was an alto sax player who was reputedly a teacher of Charlie Parker and ran a territorial band. Then in 1949 I started playing with Walter Brown; and John Jackson had come back from New York, he'd been playing with Billy Eckstine. We recorded on October 31st 1949 - my first record - it's been released in England. The next day Ben Webster was in town and he made a record date and that's how I first met Ben Webster. From there we used to have a little quartet around town and Ben used to come and sit in with us, and we'd play, and that's how I got to know Ben. After which I went to Chicago. I got to Chicago in 1951 and I stayed round there, and I was playing with all the blues bands - you know the Chess Records with Willie Dixon he was a writer of all those songs. “

“I made records for Chess with Willie Maybon, Lowell Fulson, Chuck Berry, Jimmy Witherspoon; all the blues people . . . also Otis Rush. While I was there Ben came back, and he took me up to Elkhart to get my horn fixed up and all that kind of thing. So I left Chicago and went to New York in 1957 and I ran into Ben again. And I moved out to where Ben was living - out on the Island, he invited me out there. There was this lady rented three rooms in the basement and a fellow named Big Miller who sang the blues, he lived there. So there was Ben and myself, and during that time I made a record with Ben. It was Ben's record date: The Soul of Ben Webster and Ben played a tune on that for me called Ash. Ben took me up to the Apollo Theatre and introduced me to Duke Ellington that was around 1958 sometime.”

“I met Johnny Hodges and the rest of the fellas in the band. Around 1960, I used to work in the Celebrity Club with Milt Larkin, then Duke called me up on the 'phone one morning. I got home late one morning and Duke called me on the 'phone about 8 o'clock - I've told this story many times - I didn't believe it was Duke you know. And he says “Yes this is Duke” and I hung the 'phone up, and he called back again. I lived on 925, 156th and Saint Nicholas, Duke lived on 935, right next door, and I didn't know that. And the bus (band coach) used to leave from 155th and Saint Nicholas. So Duke told me to go down and catch the bus - he wanted me to work on a Monday and Tuesday night. Anyhow I went on down and I played. You know Procope was the first one to come up on the bandstand that night and I came on and he was sitting there. You know I hadn't had too much experience playing in a big band and so I was looking at the music, and Procope said “you know this band isn't like any other band - you just blow!” So down the line the singer sang some blues and Duke told me to play, so I went on and played.”

“After that I was substituting there off and on from 1960 on. I made one record with Johnny Hodges called The Smooth One and it wasn't released until 20 years later! And Inspired Abandon - Lawrence Brown's co-leading with Johnny Hodges. In 1963 I did the My People show and after that I started working with Duke regularly on July 5 1968 when Jimmy (Hamilton) left. So I stayed there until Duke died. We played Westminster Abbey, you know the sacred concert, and we played a command performance for the Queen, that was television, and the Eastbourne performance - the 70th birthday anniversary and all these things, and I left in February 1975. Duke died on May 24 1974 so I stayed until the band came overseas and then I left.”

“I decided to leave and go on my own, a whole lot of things contributed to my leaving but that's one of them. I could tell you a whole bunch of reasons why I left, but it doesn't matter and anyhow everybody would tell you why they left and it depends how they tell the stories - the way they want to tell them. It was Duke Ellington's band and when Duke died it wasn't his band anymore! I travelled all over the world with Duke Ellington. I went everywhere, you name it: Japan, Ethiopia, I went to Poland, Russia! - all these kind of places. Yes I travelled all over the world - here's a picture of me visiting Ben at his house in Copenhagen. I hadn't been anywhere and I learned a whole lot. And Duke was a great man, a great individual. In Westminster Abbey you know that was the beginning of the time when he was sick, all the cameras were flashing in his eyes - he didn't like that. So Duke hollered at me! When we went to Copenhagen I was up there asleep and Duke called me on the 'phone about 11 o'clock, he told me to come down, and he said “you know nobody's perfect” and I said: “well Duke I know that!”ull Ó and he said “'cos there's only one perfect being.” And in other words I believe that was his way of apologising, 'cos that's the type of person Duke was. You never forget things like that. Him and Johnny Hodges . . . all them people were great people.”

What have you been doing since 1975 I asked him. Have you been freelancing all over the world? “I've been freelancing over here, the record you were talking about, Scufllin' I made in 1978, when I came over here with Cat, Booty Wood, Norris Turney, Aaron Bell and Sam Woodyard and Raymond Fall played the piano as a tribute to Duke Ellington and we recorded. Another record I made was for Progressive: Presenting Harold Ashby.”

As you may have guessed, Harold Ashby is one of a kind; whilst highly praising his colleagues and contemporaries, he reveals a great humility for his own work. Almost apologetically I told him that his style to me was a booting full-blooded mainstream tenor, but I appreciated that musicians were possibly not happy with the musical compartments into which critics and writers put them for the sake of identification. However he agreed with me . . . “Duke's book, Music Is My Mistress, has a good description of me on I think page 403. I was raised up like that - the feeling, the booting type of playing, the beat thing . . . I'm 60 years old so that's the way I play, and I believe you play the way you feel, that's your prerogative. I played with the Sy Oliver band when I left the Ellington Band for about seven weeks you know, I subbed (depped), and played with Benny Goodman a couple of times.”

Had he played in England other than with Ellington? “No, I would like to but I don't know anyone and I suppose they don't know me. I wrote about coming for the Duke Ellington Conference, but they wrote me they didn't have any money so . . . But I'm too old now, to go bothering about it no more. I just stay at home and I get enough jobs. You know Milt Hinton had a month at Michael's Pub celebrating his birthday, and I worked a couple of nights there, he invited me. You know I survive, gigs here, gigs there. You know this my first time in Nice!” I asked him how he found the audiences at the festival: “Well they are interested in jazz certainly but . . . if you don't play the beat . . . I mean if you play the blues then you can move them all the time. You can run up and down and all over your horn, you can play all the exercises in the world but if you haven't got the feeling then you don't move them. Of course you have to have a bit of knowledge and technical ability to express yourself. It's like language - you have to study the English language to talk, but you can get by with a few words.”

Do you like to play the blues? I asked him. “Oh I like to play anything”. Small groups, did they give him more space? I asked. “Well, ah .. . yes I like to play by myself because you have time to express yourself. On the bandstand with a bunch of horns, you know, you can't express yourself. It's a competitive situation even though everybody smiles and loves each other, you understand. It goes into a competing type thing. It was good in the old days, they used to jam, but it was a healthy competitive thing, you could go home and practise and get your thing together, you know. But I like to play with just Clark Terry (and the rhythm section obviously) but that kind of thing with another horn together it's a bit different from a whole bunch of horns up there on the bandstand.” (Ashby & Terry were a frequent pairing at Nice.)

“If you're playing together, in a sax section, it's different. In a band it's beautiful playing that music and everybody blending. I enjoy playing anything it's a good therapy, music. You know some people liked the Ellington forties band and some liked the sixties band, but I believe Duke matured with his writing. If you put on some of these old records you'll see that. I think all of his music was beautiful but if you listen to that third sacred concert with Alice Babs singing that music was beautiful. And Duke knew his men, their styles, and what they played best and he wrote that music for them. Everything he wrote was all right and I was very fortunate to be able to play with him. I got there through Ben Webster, you know Ben took a liking to me 'cos I was from Kansas City - home, One of the big things I played with Duke was on the Afro-Eurasian Eclipse album and another in The New Orleans Suite. This business you know it's not about playing, but about who you know! Well you know, it is about playing, but if you know somebody who's got some money well that's it. And I don't know too many people”. I think that Harold Ashby would be a great hit in the UK. His forceful, swinging, essentially hot style, would be very acceptable to jazz enthusiasts and all we need is for one of our bookers to bring him over. As he modestly says, he doesn't claim to be a 'great' but he plays as well as anybody else, and his background proves this. I have no doubt that anyone who was fortunate to hear Harold Ashby in Nice would say 'amen to that' and I for one, look forward to hearing him again, in the not too distant future.